Run The Series: GODZILLA (The Showa Era, 1954-1975)

A collections of reviews and random thoughts regarding the films in Toho's original golden age of The Big G.

NOTE: Don’t worry (or I’m sorry), this is all about the original Japanese versions, not any of the English dubs, including the King of the Monsters! version of the first Godzilla that recut the film for American audiences, which I have omitted entirely.

All subs, no dubs, baby! The way that God(zilla) intended…

GODZILLA (1954)

★★★★½

“Godzilla was baptised in the fire of the H-bomb, and survived. What could kill it now?”

Ahead of when I watched the widely acclaimed Godzilla Minus One, and in light of the shameful fact that up ‘til that point I had only ever seen the 1998 and 2014 American Godzilla remakes from Roland Emmerich and Gareth Edwards respectively, I figured it was about time I finally got around to acclimating myself to the franchise’s roots by going back to the very beginning, and properly seeing Ishirō Honda’s 1954 original Godzilla at long last.

It took me 30 years to get there, but I think I had to go the long way round through life to reach that specific moment in time, where I was old enough to better comprehend the scale and horrifying gravity of the evil inflicted against Japan by America’s nuclear bombings, particularly in our post-Oppenheimer world freshly reminding us of the mortal and existential threat posed by the creation, proliferation, and hoarding of nukes by numerous nations locked in the death spiral of their paranoiac zero sum game of mutually assured destruction. With all of that in the back of my mind, plus the historically contextual knowledge that this Godzilla is unquestionably hugely informed by it having been released only 9 years after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (the latter of which is explicitly alluded to by name in the film), this altogether made the film hit harder for me now than it would’ve done if I’d first seen it as a child or a teen, who would’ve dismissively discounted it as just some silly, dated, man-in-a-rubber-suit monster movie.

The imagery conjured by Godzilla’s warpath of apocalyptic destruction is not only redolent of those infamous old film reels of atomic bomb blasts obliterating empty test houses with fearsome shock waves of irradiated fire, but is also eerily pre-reminiscent of disasters that wouldn’t happen for decades to come. Like the scene where they try electrocuting Godzilla by surging the power lines, and the humans are doing so within a room that looks a lot like the control room from the Chernobyl nuclear plant, while wearing outfits that resemble what the Chernobyl plant workers wore when they accidentally unleashed an intangible monster of radioactive death upon the world. Or that one moment during Godzilla’s attack on the heart of Tokyo, where a shot of the jagged and smoking remains of one demolished building looks unnervingly similar to what the burning remnants of the World Trade Centre towers would look like almost half a century later, “all twisted metal stretching upwards” (to quote Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s ‘The Dead Flag Blues’).

The film’s sombre tone takes its premise deadly seriously, painstakingly caring to depict how a post-war Japan, still freshly reeling from the longterm traumas of the A-bombs’ aftermath, might realistically react to the threat of a Lovecraftian monster from the vast, dark, literally unfathomable depths of the ocean, disturbed from its ancient slumber by mankind’s warmongering scientific innovations, being set free to destroy whatever gets in its way. From the radio and television newscasts of distraught victims and refugees crowded in makeshift hospitals, to the choir of children hauntingly singing a song of tribute and despair for the deceased, all the way through to the complex, un-winnable moral quandaries presented by the solution to stopping this unstoppable monster, via the film’s very own Oppenheimer-type figure distraught by the potential world-ending applications of his own invention, all makes the OG Godzilla not just a genre-defining monster movie classic, but an invaluably essential time capsule that stunningly bottles some of the raw emotion of what it felt like to live in that post-Hiroshima and Nagasaki era.

GODZILLA RAIDS AGAIN (1955)

★★½

- “Dr. Yamane, our supposition was correct. It's the worst possibility of all.”

- “So, there's another monster besides Godzilla?”

- “That's right. The hydrogen bomb test awakened Godzilla. Now, Ankylosaurus has also been roused.”

- “Ankylosaurus?”

- “That's right. This is an Ankylosaurus. It's also known as Anguirus…”

Broke:

“Top Gun: Maverick’s third act rips off the finale of Star Wars!”

Woke:

“Top Gun: Maverick’s third act rips off the finale of Godzilla Raids Again!”

KING KONG VS. GODZILLA (1962)

★★★

- “Where should we evacuate to?”

- “Where? Somewhere safe, of course!”

- “It’s one thing to run from a typhoon, but with Godzilla and King Kong, you never know where to go.”

So I guess the scene in Kong: Skull Island, where Kong chowed down on a giant squid/octopus, wasn't (just) a nudge-wink reference to Oldboy, but was maybe also a nod to a similar moment from this, the original King Kong vs. Godzilla?

Neat, if true!

Something else that would also be amazing if it's historically accurate (which it is purported to be, but I add this cautious caveat just in case) is that - according to IMDb, and the Toho Kingdom website quoting the book, Japan's Favourite Mon-Star: The Unauthorised Biography of The Big G - when they were promoting King Kong vs. Godzilla, Toho released so-called "interviews" given by the eponymous monsters, trash-talking each other before their big fight as if this was the run-up to a WWE smackdown.

Godzilla was “quoted” (inasmuch as you can quote a monster who doesn't talk in words, and is also entirely fictional) as saying the following, which I encourage you to imagine being spoken in the voice of Macho Man Randy Savage:

“Seven years have passed since I rose from the bottom of the southern seas and raved about in Japan, leaving destruction behind wherever I crawled. It is most gratifying for me to have the privilege of seeing you again after breaking through an iceberg in the arctic ocean where I was buried. At the thought of my engagement with King Kong from America, I feel my blood boil and flesh dance. I am now applying myself to vigorous training day and night to capture the world monster-championship from King Kong.”

King Kong's “response” was this, which I encourage you to imagine being spoken in the voice of Hulk Hogan:

“I may be the stranger to the younger people here, but have quite a number of fighting adventures to my credit. I will fight to the last ditch in the forthcoming encounter with Mr. Godzilla, for my title is at stake... Hearing that the world-renowned special effects director Eiji Tsuburaya is to act as referee, I am going to return to the screen in high spirits.”

Incredible stuff.

The film itself? Eh, it has its charms, as all these endearingly silly films do. The parts with the dated depiction of natives from Faro Island (the new home of Kong, because perhaps Toho couldn't call it "Skull Island"?) feels racially insensitive in ways I'm not equipped to articulate, nor have any authoritatively expert stance on. Plus, while I don't hold it against them, the monster effects implemented to bring Kong to life are rather hokey.

Yet even so, it's a marvel to look back on these movies, and watch them through the perspective of filmmaking problem-solving, given the limitations of technology, time, and money they had at their disposal to bring these gargantuan rock-'em-sock-'em kaiju battles to life. From the men inside the Godzilla and Kong suits throwing themselves around small-scaled sets, to the miniatures and models of buildings and trains and tanks and even people, not to mention the occasional bit of stop-motion and hand-drawn animation, it's endlessly charming to see the myriad techniques they used to use to create sequences we'd nowadays render almost entirely in CGI.

Also, the satirical, slyly meta aspect to the plot, where bringing Kong to Japan and eventually pitting him against Godzilla is all because of cynical corporate advertising interests looking to capitalise on the ratings and money such a spectacle would bring, is wonderfully cheeky.

Kudos to the denizens of the Internet Archive for providing the best avenue available to watching this film whatsoever, seeing as it's not on any streaming services, nor or are there any... um, shall we say, “sea-faring” options of a good quality version of the original Japanese language cut. (No way in hell am I willingly watching any dubs over subs.)

The version I watched can be found HERE, whose subtitles included very helpful contextual information that clued me in to a couple of culturally specific wordplays or references that would've otherwise gone over my head. (For instance: the cartoonish boss of Pacific Pharmaceuticals, who sends his two bumbling employees to Faro Island, is named Mr. Tako; tako is also the Japanese word for octopus; so when the giant octopus starts attacking the Faro Island village, the two men get into a “who's on first?”-style miscommunication where one of them's talking about the giant octopus outside, and the other thinks they're talking about their boss. Hilarity ensues. The other example: a character believed to be dead returns to his home, and his neighbour sees him, but thinks he's a ghost, remarking that she didn't expect to see him with legs. A subtitle then handily notes that in Japanese folklore, ghosts are believed to be literally legless beings, whom you can only see from the torso up.)

However, that version has a tendency to fluctuate in picture quality, due to how it alternates between the well-preserved negative that the American re-edit was made from, and the unwell-preserved negatives from the full Japanese cut. Only after I'd watched it, and saw on IMDb that there was a full 4K restoration made of the full Japanese cut's rediscovered 35mm print, did I check for this potentially better-quality version, and sure enough, there it is on the Internet Archive as well, with English subtitles attached to the MKV file and everything! So if you want to see a better print of the film than even I watched for this review, check that out HERE.

MOTHRA VS. GODZILLA (1964)

★★★½

- “But Godzilla's on a rampage. Japan's in great danger!”

- “It's your fault for playing with the devil's fire! It's no concern of ours. This island was once a beautiful place... a peaceful, verdant island. Who ignited the devil's fire here? The fire forbidden by the gods!”

For what it’s worth, Shobijin and Shobijin, the adorable singing fairy twins from Infant Island, are thus far the only twins in all of cinema who don’t creep me out by always uncannily speaking in unison, which is a grand achievement if I do say so myself.

GHIDORAH, THE THREE-HEADED MONSTER (1964)

★★★★

- “Mothra's talking to them. What do you think she's saying?”

- “How would I know? I don't speak monster!”

If I may so tastelessly apply an analogous comparison between the original Toho Godzilla franchise, and the Marvel Cinematic Universe:

Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster is to the Toho MonsterVerse what Thor was to Marvel - i.e. if this movie succeeded in getting you get on board with the idea that fantastical alien beings could co-exist in the same universe as the fantastical earthbound beings you’re already familiar with, then there’s virtually no limit to where this series of films can go, and what they can do.

Simultaneously, Ghidorah is equally equivalent to the first Avengers - i.e. teaming up a collection of the studio’s previous iconic characters into one movie, having them put aside their differences, and work together to take on an alien threat that’s bigger than any one of them could handle alone. Except, rather than Iron Man and the Hulk and Thor and so on, here it’s freaking Godzilla and Rodan and Mothra having to join forces to defeat evil three-headed space-dragon, King Ghidorah.

Oh, and while Toho are at it, they also throw extraterrestrial possession, dimension-slipping, and an attempted political assassination plot into the mix, to keep the human drama just as wild, yet still highly involving.

We may be straying ever farther from the franchise’s sombre nuclear-fearing roots by this point, but in this colourfully emboldened era of rubber monsters beating each other up for the spectacle and wonder of it all, one can’t help but be swept along in the wake of the series cutting loose from the horrors of reality, and charting its own joyous course into the realms of sci-fi fantasy.

INVASION OF ASTRO-MONSTER (1965)

★★★

“We need an exterminator, one that would drive away King Ghidorah. We need from you Monster Zero 1 and Monster Zero 2 - Godzilla and Rodan.”

I might have theorised that Invasion of Astro-Monster was another one of the many pieces of fiction Ernest Cline ripped off whole-cloth plot points from when he wrote his second (terrible) novel, Armada - what with the technologically advanced, allegedly benevolent aliens offering earthlings a cure for cancer, and mutually beneficial cooperation between species, which may or may not be a ruse to take control of Earth - but I think that would be giving Cline too much credit, because I doubt his knowledge extends much past the superficial trappings of trivia he knows about 1960’s Western pop culture, and that’s just because the 60’s was the decade Doctor Who and Star Trek: The Original Series began.

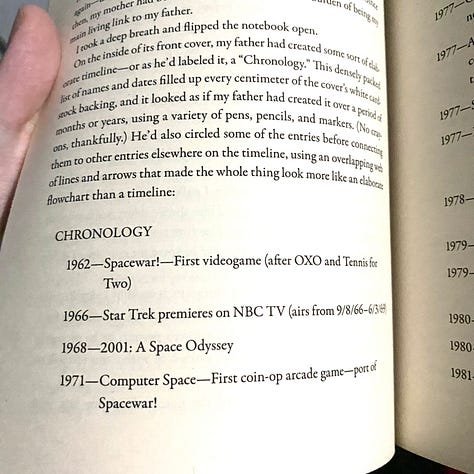

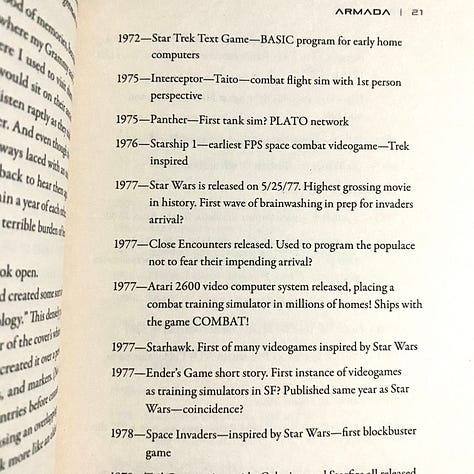

After all, in Armada, Cline makes the stunningly stupid assertion that the notion of extraterrestrials and/or alien invasions pervading the societal consciousness only goes as far back as 1962, with the game Spacewar!, followed by Star Trek in 1966, then 2001: A Space Odyssey in 1968, and after listing some other obscure games, he writes two of the dumbest paragraphs ever written by a “professional” author:

“1977 - Star Wars is released on 5/25/77. Highest grossing movie in history. First wave of brainwashing in prep for invaders arrival?

1977 - Close Encounters released. Used to program the populace not to fear their impending arrival?”

This is all to lay the groundwork for Armada’s premise that, for decades, after the discovery of alien life and the looming threat of an eventual invasion, the world’s governments have been working with multiple factions of the entertainment industry to slowly ingratiate the public to the idea of aliens attacking Earth, while also covertly training the public to fight back in this eventual war by conditioning generations of people through video games to know how to instinctively use military drones to shoot down the alien forces.

But here’s one of the biggest canyon-sized holes (though far from the only hole) in Cline’s preposterous plot:

WHAT ABOUT THE DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL?

WHAT ABOUT INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS?

WHAT ABOUT ROSWELL, NEW MEXICO?!

WHAT ABOUT AREA 51, YOU MUPPET??!!!!?!

WHAT ABOUT H.G. WELLS’ THE WAR OF THE WORLDS, WRITTEN IN 1898??!

ARE YOU SAYING NONE OF THESE - AND MORE - HAD ANY BEARING ON THE PUBLIC’S AWARENESS, FASCINATION, AND OBSESSION WITH ALIENS?!!!

DO YOU REALLY THINK THE WORLD AT LARGE ONLY STARTED THINKING ABOUT ALIENS BECAUSE OF STAR WARS???????

So yeah, my guess is that Ernest Cline didn’t take this idea from Invasion of Astro-Monster, but probably pinched it from V: The Miniseries and V: The Final Battle, because they both aired in the 80’s, and that’s his favourite decade for pop culture, bar none. (Though as he revealed in a featurette on the Blu-ray extras for Ready Player One, he knows next to nothing about horror movies, and seeing as the 80’s were one of the greatest decades ever for the genre, how can you be a purported scholar of 80’s cinema, and leave the horror movies of the time out of your consideration? That’s like saying you painted your entire house, when you only really covered the outside, and neglected everything left to cover on the inside.)

Now I know what you’re thinking: what the hell does any of this have to do with what I thought about Invasion of Astro-Monster?

Answer: almost nothing! At least not right now. In future, maybe I’ll look back at my viewings of all the old Toho Godzilla movies, and the more unusually oddball things will belatedly strike me with their strangeness, like the plot turning out to pivotally hinge on what’s essentially a high-tech rape whistle, or the weird hints of the Xilians’ lore (what with everything they do being dictated and calculated by computers; their planet lacking in water, yet rich in gold; all the females of the species being an exact replica of one another; etc). But in the world of old-school Godzilla, all of the oddities kind of blend into each other, and are just another part of this crazy world of gods and monsters… or rather, gods who are monsters.

Godzilla doing that gloriously absurd and joyous jig in reduced gravity is a delight to see, however.

And the moment when Godzilla and Rodan are left behind on Planet X, ruefully watching as the humans fly away on their ship, the monster antiheroes shrinking into distant specs on the planet’s surface, is one of the most unexpectedly moving moments any of these films have had, where you feel more for the monsters than you do for the humans who take up the majority of the story.

EBIRAH, HORROR OF THE DEEP (1966)

★★★★

- “Safecracking must be easy work.”

- “It just looks that way to amateurs.”

The changeover from longtime Godzilla director, Ishirō Honda, to the next most prolific director who worked on the Toho series, Jun Fukuda, results in Ebirah, Horror of the Deep feeling like a rejuvenating shot in the arm for the franchise. It’s hard to pinpoint precisely how, but there’s just something about Ebirah’s particular amalgamation of things that past movies in the series have done so well - i.e. interesting characters, spectacular miniature special effects, charmingly old-school creature effects, an unusual yet involving plot, great music (though here alas sans the themes of Akira Ifukube), and themes of anti-war and anti-colonialism - but all done with a touch more zeal and zest.

Maybe it’s the focus on moments of real suspense, ratcheted up by the clever sound design, and the tension we feel for characters we care about getting out of these sticky situations alive. Maybe it’s the ever-so-slightly different, dynamic eye for visuals Fukuda delivers through the ways scenes are blocked, shot, and edited, with a newfound adoration for the odd Dutch angle here and there. I don’t know! But there’s an elusive, undefinable quality to Ebirah that scoots it up a notch in my rankings among these films.

And that’s even with the goofier elements in mind, such as when Godzilla looks at a human character, and does his version of that thing where you cheekily tap the side of your nose twice (no, really), or when Masaru Satō’s battle music, for the showdown between Godzilla and Ebirah, suddenly morphs into upbeat twangy surf-rock.

More than anything, Ebirah, Horror of the Deep felt the most like an early James Bond film than any of the Godzilla series has up until now. Certainly not with regards to the sole woman among the mainly male ensemble, who, if she were in a Bond movie, would’ve automatically been allocated the formulaic function of love interest/eye candy, but herein is refreshingly neither. No, what I’m referring to is that this film’s primary setting of an island paradise, crossed with a villain’s ginormous secret base for nefarious purposes with massive Ken Adam-esque interiors, makes me think of Ebirah as like if Dr. No included a couple of duelling kaijus, or like if You Only Live Twice was actually good.

(Ironic that I should think of that film, since You Only Live Twice featured the stunningly beautiful Akiko Wakabayashi, who just so happened to have previously appeared in King Kong vs Godzilla, and Ghidora, the Three-Headed Monster, as two completely unrelated characters, such was the way with seemingly all the actors who turned up in multiple Toho MonsterVerse movies, never playing the same role more than once.)

SON OF GODZILLA (1967)

★★★½

“Godzilla and son, Kamacuras, Kumonga… this should be called ‘Monster Island’!”

• Between Mothra the giant moth, and Kumonga the giant spider (Jon Peters, get outta here!), I bet Godzilla must be getting pretty peeved by this point with getting constantly sprayed with other monster’s webbing (non-euphemistic) all the time.

• Is it too much to hope that one of the sequels will break tradition, and actually feature a returning human character? Because I’d love to see Bibari Maeda’s Saeko have her story followed up on, to see how she’d react to seeing civilisation for the first time after having lived on that island all her life. But alas, judging from Godzilla films past, and from the dearth of credits to Maeda’s name in her overall filmography, I’m guessing this is a pipe dream that’s 60 years too late to ask for. Who knows? Maybe there’s some (non-Rule 34) fanfic out there that imagines this sequel idea for me? But anyway, I digress.

• I gather from the film’s average Letterboxd rating of 2.7 out of 5 stars, and the general consensus of reviews I’ve glimpsed, that Son of Godzilla is looked at rather unfavourably by a lot of fans of the series? Is it because of Godzilla’s spawn himself, and that people find him annoying, cutesy, or annoyingly cutesy? I don’t know what it says about me, but I quite enjoyed this fun little romp, and I wasn’t put off by the eponymous little tyke. He’s as annoying as he is cute, just like any toddler, and I found the father-son bonding between him and the OG Big G to be wholesomely heartwarming, and by the end, unexpectedly poignant. I could just be getting soft in my old age, but hey, it is what it is.

DESTROY ALL MONSTERS (1968)

★★½

“There isn’t a cloud over Mount Fuji today. The mountain and surrounding Aokigahara forest are silent. But the monsters will soon launch an all-out assault on the Kilaak’s base. This is the calm before the storm. Defence forces are in position. Still no sign of the monsters. Who will arrive first? Godzilla? Rodan? Anguirus?”

You read that right - the big multi-monster showdown in Destroy All Monsters does, in fact, take place near “the Sea of Trees”, a.k.a. the notorious “suicide forest”.

What do you, or I, even do with this information?

Hell if I know.

But that isn’t the reason for my relatively low rating of this otherwise widely beloved entry in the Godzilla canon.

No, my rating stems from how - up until the climactic epic all-stars team-up battle, featuring nearly a dozen monsters, which is well worth the proverbial price of admission - Destroy All Monsters suffers from its first two thirds dragging the entire film down. The plot is overstuffed, repetitious, and occasionally rendered incoherent in how rushed and contrived things are made to be by the lacklustre writing. In the ensemble of human characters, we don’t get anyone to latch onto or care about. Characters frequently make irritatingly stupid decisions (like in the opening scene, where instead of running away from the suspicious gas leaking through the door, the characters run toward the gas, and open the door, before they think to keep away or look for gas masks; or the scene where the two guys are interrogating the seemingly alien-brainwashed scientist, then they take a cigarette break, and just watch the man casually walk to the window, open the curtains, open the window, and jump right out to his death, without them ever thinking to move and stop him at any moment before that). The general plot is basically Invasion of Astro-Monster again, but instead of the Xilians, it’s the Yeerk-esque Kilaaks, whose collective smugness does at least make them villains you love to hate.

It’s not until the eventual monster royal rumble finally arrives that the film livens up into an undeniably sensational spectacle that (almost) makes the messy preamble to get there ultimately worthwhile.

My apologies to any Destroy All Monsters fans out there for diverging from the consensus opinion. I wanted to like it as much as the glorious promise of its premise geared me up for, but alas, it just didn’t click for me. And considering that this marked a return to the fold from the erstwhile mainstays of director Ichirō Honda, and composer Akira Ifukube, not to mention was pitched as an ostensible send-off to the whole series, that’s a damn shame for me to say.

But of course, in the same way this wouldn’t be the last time Godzilla paid a visit to New York on the big screen, this was also obviously never going to be the final Godzilla. Oh no, faaaaar from it…

ALL MONSTERS ATTACK (1969)

★★★

- “The moon is great, but there's somewhere else I'd rather go.”

- “Where?”

- “Monster Island.”

- “Monster Island?”

- “Yeah. Minilla, Godzilla, Rodan, Kumonga, and lots of other monsters are there. They're all stronger than Gabara.”

- “Gabara? Never heard of that monster.”

- “I mean Sanko, the bully.”

For a movie whose existence was predicated on how cheaply and quickly it could be made (what with it shooting on real locations, downgrading in tone into a full-on children's movie, and eschewing newly-made monster fight scenes in favour of repurposing old footage from Destroy All Monsters, Son of Godzilla, and Ebirah, Horror of the Deep, which take up unduly large swathes of this film's already slender, barely feature-length 69 minute runtime), and whose reputation reportedly ranks it among the very worst of all the Godzilla movies ever made...

...I've got to say, I liked it a fair bit.

I mean, yeah, the parts that are just hastily stitched-together, shamelessly recycled stock footage excerpts from previous films, are somewhat tedious to sit through, as you can feel how disconnected they are from the wraparound narrative of Ichiro, the child protagonist, fantasising he's witnessing these old fights in person, while his idolised fantasy friend, an extra-mini Minilla, speaks to him in human words.

And yet, in the real-world sections of Ichiro's wraparound story, there's some genuinely compelling stuff going on. A latchkey kid, lonely and bullied, left to fend for himself after school while his parents are at work, striving to make enough money for them all to one day leave behind the polluted air of the industrial urban sprawl of their city. A young boy who daydreams about meeting the fabled monsters who have become mythic figures of awe and worship. All of this punctuated by the subplot of a couple of thieves who've stolen away with fifty million yen, who of course soon figure into the life of the young boy we've followed the whole movie.

Ishirō Honda may have shot this all on the cheap, but the penny-pinching need to shoot on location gives the real-world sections of All Monsters Attack a grounded verisimilitude of ordinary reality that past Godzilla films often opted out of, in favour of the abiding visual style of models and miniatures selling the behemoth giganticness of the rubber-suited and/or puppeteered monsters. Couple this small-scale, slice-of-life social drama, with the moderately darker tone Ichiro's story takes as his path inevitably crosses with the bumbling but ruthless thieves, and suddenly this is a Dickensian fable! Practically a slice of Japanese neorealism in the vein of Yasujirō Ozu, but with occasional detours into childlike fantasy where our main character's wishes and fears are represented by assorted kaijus beating each other up, while Godzilla's son and Ichiro go on parallel journeys of discovering their inner strength and resolve to survive against those who wish them harm.

It's good stuff! Positively Spielbergian in its ambitions, but made over a decade before Spielberg or any 80's American movies made this kind of movie all the time! And if you can forgive the prolonged scenes of replaying the greatest hits from Godzilla films past, you ought to find that All Monsters Attack is a bit of a gem in the rough.

GODZILLA VS. HEDORAH (1971)

★★★★

“The atomic bomb and hydrogen bomb cast their fallout into the sea. Poison gas and sludge gets dumped in the ocean. Even sewage. I bet Godzilla would be mad if he saw this.”

Before it reaches its nuclear-powered flying form, Hedorah's evolution into a gloopily grotesque tendril-covered red-eyed eldritch nightmare makes it the closest that Godzilla has come to fighting actual Cthulu. And although laying one's eyes upon Hedorah doesn't immediately drive the human psyche into irretrievable madness like the sight of Cthulu would, Hedorah is still enough of a Lovecraftian cosmic abomination to make it one of the most fearsome foes in all of Godzilla's rogues gallery.

That Lovecraftian factor feeds into Godzilla vs. Hedorah's admirable return to the franchise's darker roots, of man-made monsters striking a palpable mortal fear into the hearts of the humanity that spawned it through our own hubris and planetary destruction. Where once Godzilla was awakened by our nuclear bombs, Hedorah is birthed from an extraterrestrial minuscule life-form that evolved and exponentially grew by feeding off of our toxic sludge and industrial pollution poured into the sea and the air. And from this living, breathing, walking morass of cancerous smog and factory filth, Hedorah delivers unto us multiple moments of truly upsetting, nigh-on full horror imagery, where death and destruction has a visibly human toll again.

It starts right from the opening credits montage, featuring that jaunty song and its bleakly apocalyptic lyrics, with that one primordially unnerving image of a mannequin broken apart, lying among the detritus floating in the toxic waste coating the sea's surface, looking disturbingly close to a real human having been cut into pieces and dumped in a polluted river. This gets mirrored later in the film when a house full of people gets flooded with Hedorah's excess sludge oozing off it at all times, and director Yoshimitsu Banno chooses to hold on the stark, quietly horrifying image of the house half-filled with the deadly sludge, its surface punctured by the frozen limbs of the people consumed beneath it. Yet even with later instances of seeing Hedorah having the power to kill people by spraying acidic mist that burns and melts people en masse down to nothing but skeletal remains (seriously, this movie goes hard), the one image that haunts me most is the moment when Hedorah's sentient sludge withdraws its invasion of a psychedelic nightclub, leaving behind only its residue on the floors and walls, and a small, scared cat that it had swallowed and spat back out, leaving it dirty and shivering and mewling on the stairs in fright.

From what I've gathered via the Criterion Channel referring to this as a “divisive” entry in the Godzilla franchise, and from Wikipedia's abridged history of what the reaction to the film was contemporaneously and retroactively, it seems Godzilla vs. Hedorah is an extremely your-mileage-may-vary kind of film, to put it mildly. Some are very receptive to its blend of psychedelia in its imagery and music, its abstract animated segments, its examination of the psychological impact Hedorah's destruction wreaks on a micro and macro level, and the massive tonal shift towards apocalyptic monster horror, leaning quite a ways away from the goofily fun histrionics most of the series had steered into as Godzilla reached the insanely popular heroic icon status he'd achieved since Ishirō Honda's original film 17 years prior. And others are decidedly not receptive to its charms, unable to vibe with its particular wavelength.

For me, however, this was exactly my cup of tea, and I think Godzilla vs. Hedorah ranks pretty close to the first Godzilla, and certainly high among the best sequels that came earlier in the series, right up there with Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster, and Ebirah, Horror of the Deep.

GODZILLA VS. GIGAN (1972)

★★½

“They’re not human. They’re insects from another planet. Monster cockroaches from space!”

Godzilla vs Gigan is barely more than a greatest hits compilation of Godzilla movies past, rehashing old ideas, old plots, old music (by way of repurposing Akira Ifukube’s previous scores without his involvement, resulting in such bunglings as his themes for Godzilla and Rodan being used for scenes featuring neither Godzilla or Rodan), and even old footage of old monster battles, to make up for the decreasing budgets these movies were receiving from Toho in the waning years of the Showa era.

Gigan has its moments, but it feels like it suffers from an identity crisis, brought on by the apparent mixed reception to Yoshimitsu Banno’s standout preceding entry in the series, Godzilla vs Hedorah. In a similar fashion to The Rise of Skywalker being a studio’s reaction to the audience’s reaction to The Last Jedi, it feels as though Godzilla vs Gigan is a reactionary attempt to course-correct back towards appeasing fans let down by Godzilla vs Hedorah, but somewhat fumbling the bag in the process. Like, Gigan is too goofy to be fully for adults (e.g. enemies-turned-homies Godzilla and Anguirus talking to each other with comic book speech bubbles translating their words), yet also too violent and surprisingly bloody for young kids (and when I say bloody, I mean Tarantino levels of crimson blood-sprays coming out of these monsters in their extra brutal fights).

Still, at least I have my head-canon that, with this film’s antagonistic aliens who look like cockroaches in their natural forms, Godzilla vs Gigan can act as a quasi-prequel to Team America: World Police, explaining where the alien cockroach inside the marionette Kim Jong Il came from…

GODZILLA VS. MEGALON (1973)

★★★½

- “Look, you're sure you want to go? Could be damned dangerous.”

- “I know, but I built that robot myself. I feel responsible.”

- “So he's like a son? That's very touching.”

Contrary to what I had misremembered as a piece of true trivia, the record label Jagjaguwar - home at various times to the likes of Bon Iver, and Sharon Van Etten - didn’t get its name from someone mishearing the name of Godzilla vs Megalon’s newly introduced robot character, Jet Jaguar. So that’s my bad.

Anyway, despite this film’s flagrant recycling of footage from the previous Godzilla vs Gigan - with moments of cityscape destruction reused wholecloth, and the new baddie Megalon shooting bolts of yellow lightning from his head, seemingly just so it could somewhat match King Ghidorah’s characteristic yellow lightning bolts that can be plainly seen in the stock footage he’s been cut out from - Godzilla vs Megalon is actually a lot more entertaining. There’s a couple of exciting scenes of hand-to-hand combat, a viscerally thrilling car chase that looked rather genuinely dangerous to film, and a better sense of human peril that makes it easier to care for our trio of protagonists, thrown into a plot involving an uprising from an ancient underwater civilisation taking revenge on the surface world’s destruction of the planet. (That’s right, we’re going full Aquaman / Black Panther: Wakanda Forever up in here!)

The silliness levels are off the charts by this point, all semblance of reality thrown to the wind in favour of vibes and child-logic, exemplified by Power Rangers reject, Jet Jaguar.

They’re a robot built to be controlled by computer, and also by sonic override, until they suddenly gain sentience, morality, and free will, because… why not? And then, out of nowhere, Jet Jaguar can transform from human-sized, to kaiju-sized, because of the power of their quote-unquote “determination”??

Let’s not quibble, it’s frickin’ magic, dude, and they should’ve just hand-waved it away by saying “because magic”, because they might as well at this juncture of the Godzilla lore.

But really, how can one truly hate Godzilla vs Megalon, when this is the movie that (finally!) features that iconic moment of GIF-able royalty, when Godzilla rides along the ground on his tail to drop-kick his opponent! When that moment came, you better believe I was cheering uproariously at the awesome absurdity of it all.

GODZILLA VS. MECHAGODZILLA (1974)

★★★

- “When a black mountain appears above the clouds, a monster will arrive and try to destroy the world. The ancient prophecy is coming true.”

- “I would never have guessed... that the monster could be Godzilla!”

Is it bad that upon first seeing Mechagodzilla, my immediate thought was that it reminded me of Preston, the evil robot dog from Wallace & Gromit: A Close Shave…?

TERROR OF MECHAGODZILLA (1975)

★★★

“So this is Tokyo. It’s just like the brains of these earthlings… polluted and chaotic. Imposing order has always been an afterthought. When all is said and done, they don’t even know what they’re creating.”

And so here lies Terror of Mechagodzilla.

The final Showa Era Godzilla film (at least per the Criterion Channel collection’s designation, even though the belated following film, The Return of Godzilla, was also still technically in the Showa Era, too).

The final film from Ishirô Honda, marking this as a send off to his directorial career by way of helming a send off to the franchise he began with 1954’s original Godzilla, two decades previously.

The final time audiences would see Godzilla in his heroic protector mode, and in any official big screen capacity at all, before he’d be resurrected 9 years later in a continuity-resetting reboot that reverted him back to his villainous roots.

To be honest, the human drama herein has more interesting things to it than the monster battles do. On the kaiju side, it’s the usual bananas schlock — aliens trying to conquer Earth, a new monster to be friend or foe to Godzilla, scientists and spies with duelling agendas, yadda yadda yadda. But on the human level, you’ve got the more engaging subplot of disgraced scientist Dr. Shinzô Mafune (played by series regular Akihiko Hirata, unsurprisingly playing a completely different person from the half-dozen other characters he was in past films in the franchise), who was somehow shunned by the scientific community for positing the existence of a dinosaur (Titanosaurus) fifteen years prior, which apparently made him a laughing stock… even though, by that point in the general timeline of the movies, everyone was keenly aware Godzilla existed, so why anyone would have trouble believing in another giant monster existing simultaneously, I’ve no idea. Anyway, Mafune’s daughter Katsura (played by Tomoko Ai) winds up getting killed during one of his experiments, only for her to be reborn as a cyborg by the aliens behind Mechagodzilla, who use Katsura as a pawn to keep the doctor indebted to them; he helps them work on their plans for world domination, and in return he gets his revenge on the people who ruined his life, and his daughter gets to keep living through the aliens’ technology. Amidst all this, you also have Katsura’s burgeoning inner conflict as she grapples with the knowledge of her mechanical artificiality, and the feelings that there’s still a humanity within her breaking through.

This part of the story was of the utmost importance to the screenplay’s primary author, Yukiko Takayama (one of the very few women screenwriters the franchise has ever had), and you can feel that extra emotional investment emanate from the film. Or maybe I’m just projecting, and I only like it so much because I’m a sucker for stories about ostensibly artificial beings going on journeys that make them ask themselves if they’re more than mere nuts and bolts, and may actually have souls of their own after all. (See also: “K” in Blade Runner 2049; the Tleilaxu ghola, Hayt, in Dune Messiah; Number 5 in Short Circuit; insert countless other examples from science fiction that you can think of here.)

In any case, Terror of Mechagodzilla is a fitting end to the original run of Toho Godzilla movies, and a bittersweet farewell to the Big G’s good guy era… at least, for a decent chunk of time. But of course, it’s an inevitability that the longer a Godzilla continuity goes on for, the more inevitable it is that the filmmakers and audiences will always want to see him return as our undefeatable lizard Lord and Saviour, and I think that’s kind of beautiful.

Ashamed to say I had a film class in prison and I tried to teach "Destroy All Monsters", but I ended up with "All Monsters Attack" instead. The entire time, for some reason, I just waited for it to become "Destroy All Monsters". I don't know what I was thinking.

Fromtheyardtothearthouse.substack.com