What I Don’t Like About Astrology

(Personally speaking, from my own point of view, not to dissuade anyone else’s beliefs, you do you, etc.)

I may be a Leo, but I’d be lion if I said I felt like one.

Okay, for what it’s worth, I’d like to state upfront that I truly don’t mind those who believe in astrology, horoscopes, and all that zodiac jazz.

But just speaking for me personally, though, it’s a belief system that’s never really sat well with me.

Put it this way:

You know how in the Divergent books/movies, there’s that half-baked notion about the post-apocalyptic society being split into different personality-based factions, divided up between Abnegation (the selfless), Amity (the peaceful), Candor (the honest), Dauntless (the brave), Erudite (the intelligent), and Factionless (those who don’t complete or fail initiation into any of the groups, and are thus made homeless outcasts)? To me, that has always seemed like such a thoroughly stupid conception for a fictional world; even if it’s supposed to be flawed to show there’s some grander sinister conspiracy behind everything, it’s just too egregiously flawed from the get-go for me to believe that anybody in-universe would be silly enough to go along with it for multiple generations, let alone believe the architects of the system wouldn’t immediately realise, within a scant few seconds of thinking through its implications, that this system would just be too moronic to implement if they seriously wanted to maintain a longterm authoritarian regime.

The factions notion falls apart the moment you start to ask: “So being selfless means you can’t be peaceful? Being honest means you can’t be brave? Being intelligent means you can’t be any of those other traits? And to be Divergent is to have more than one of these traits at a time, which — SPOILER ALERT — is simply just how most humans operate? And how selfless, peaceful, honest, brave, and/or intelligent can your society truly be if you can willingly cast out and subjugate an entire amorphously-defined class of people onto the streets without food, shelter, or dignity?”

(Wording it that way, you’d think that that last point was an intentional sociopolitical commentary the books and movies were trying to make about capitalism and, by extension, homelessness, but I sincerely doubt there was any deep subtextual thought put into such a thematically shallow and vacuous series as Divergent was.)

How about the Sorting Hat system that we see enforced through the majority of the Harry Potter series, where for centuries all the children that have ever attended Hogwarts are divided across four houses (Gryffindor, Hufflepuff, Ravenclaw, Slytherin), based on whatever the magical talking hat decides is each student’s corresponding personality, and the guiding principle everyone subscribes to is that Gryffindor is coded as good/brave/honest, Slytherin is coded as bad/spineless/deceitful, and the other two houses are just kind of stuck in the middle?

It took ten years and seven books, and only in the final chapter of the final book, for it to be explicitly stated in no uncertain terms by Harry to his son that this system is inherently flawed and one-dimensional, and that being part of any one Hogwarts house is not a mark of whether a person is all good or all bad, because one of the bravest people he ever knew was a Slytherin, so his son shouldn’t be afraid of joining them if that should happen. (Yes, I know this moral was cumulatively made through a multitude of character actions, plot developments, and aggregations of nuance and details from all across the series that gradually lead readers to realise this for themselves, before Harry ever said as much in the series epilogue, but you see what I’m getting at, right?)

Or what about in the sequel trilogy of Star Wars, where Rian Johnson and The Last Jedi made the optimistic case that one’s future needn’t be defined by their past, that greatness can come from anywhere regardless of lineage, that we are bound by nothing but our own decisions, and that in spite of how you see yourself, or how others may see you, you can always choose to reject inhabiting or inflicting darkness? (Well, at least before The Rise of Skywalker came along, took a massive steaming dump on those philosophies, and said: “Nah! All is predestined, everything repeats endlessly, only people from famous bloodlines can be truly special or world-changing, and we’re all just slaves to the past! Buy my merch!”)

In its most bare-bones form, you can even boil down what I’m driving at to the first two (and still unbeaten) Terminator movies’ repeated doom-defying assertion that:

“There is no fate but what we make.”

This is essentially the crux of my argument.

Flattening the vast scope and complexity of human history, behaviour, morality, and causality, and compartmentalising all of it down into simplistic, easily digestible, easily predictable, easily judgeable black-and-white binaries is something that simply does not work for me.

At its core, I just find such a thing to be very… limiting.

Which is basically the problem I have with astrology, numerology, and other forms of pseudoscientific divination techniques out there.

It’s a kind of magical thinking that, while admittedly relatively harmless compared to other much graver ills of the world, nonetheless presupposes we’re all locked onto pathways of life that we can’t decide or control, eternally predestined from the random (or, I suppose, not-so-random) circumstances of our births.

It says we never really have much choice in what we do.

And therefore, no real free will.

(Put a pin in that, we’ll be coming back to it later…)

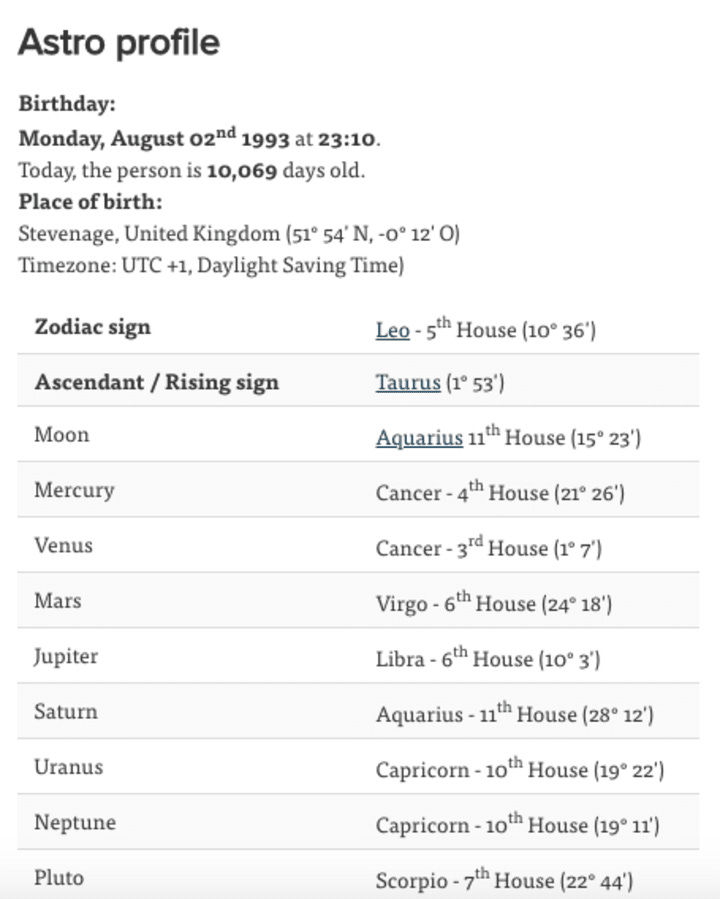

So okay. Let’s pull a Ben Shapiro (five words nobody should ever say un-ironically), and let’s say that I suspended my disbelief for a little while, and let’s say I checked what the stars apparently have to say about who I am as a person, and let’s say the results looked a little something like this:

What does all that mean?

Hell if I know.

The moment I see clusters of numbers in such close proximity like that, my brain just clogs and grinds to a halt. (It’s no wonder I got a D in my final Maths GCSE way back when.)

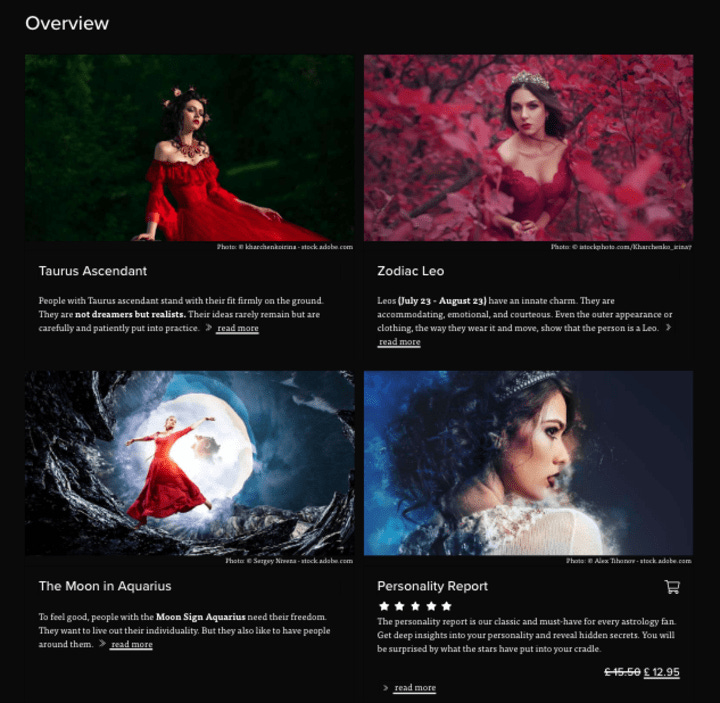

Alright then, here’s an alternate version from the same site, this time with pretty pictures and words to enliven the numbers my mind refuses to compute:

So, where to begin?

Let’s start with the Zodiac Leo reading. You can read the whole thing here should you wish, but here are the main quotes I wanted to highlight:

“If all humans are worms, then Leos are fireflies, so they stand out from the crowd.”

First of all: it should go without saying, but the phrase “all humans are worms” is weird and degrading, right? And to say people who happen to be Leos metaphorically glow brighter among the lowly worm-like crowd makes it sound as though Leos are somehow better or superior to other people, which I emphatically disagree with. Meanwhile, I can safely say I am far from unique or distinctly recognisable, as the term “stand out from the crowd” implies. I am merely average. I’m tall, but I’m not the tallest; I’m sort of smart, but not the smartest; I have immense emotional baggage, but so does everyone to their own degrees; in my prepubescent years, depending on how long my hair was, I was faintly androgynous to the point where multiple times I was mistaken for a girl (which at the time I thought was a bad thing, but nowadays know there was never anything wrong with that), and then in my adolescent years, when I looked more conventionally male, I was often mistaken and confused for other boys who looked vaguely similar to me; now in my twenties, with my shaved cranium + chinstrap beard combo, I look like a million other baldy beardy white guys with glasses. All to say that I’ve never really been a uniquely identifiable person, but merely a guy who looks like a bunch of other guys.

I am not special.

But I don’t need to be. And I’m okay with that.

Next up:

“In many cases, however, [Leos] are accused of absolutism, since they believe they are the only ones to possess knowledge. Moreover, what they want must necessarily be done. So they can be extremely stubborn and do rarely adhere to current views. Their opinion is firm and do not accept to change ideas since they are very proud.”

Not so. I am always well aware that I do not, and cannot, know everything. One guiding principle of mine is that if I have any kind of thought or idea, then in all statistical likelihood, someone somewhere has probably already had that same exact thought in the past, is maybe thinking it concurrent to me in the present, or will inexorably come to think it in the future. I don’t seek uniqueness, as that’s a next-to-impossible task that can leave you spinning your wheels, tying yourself in knots, and driving yourself mad. Instead, I choose to seek what’s emotionally truthful and fulfilling; even if it involves elements of things that have been seen or done before, as long as it comes from someplace genuine, rings true, and connects with someone, then that’s all that really matters.

As for my supposed steadfast, unchanging opinions on things, I like to think that I am always open to changing my mind, and evolving my ideologies to accommodate new ideas and different perspectives. One of the very few — actually, no, the only good thing about my lifelong troubles with self-loathing and self-doubt is that I am always of the sneaking suspicion that, at all times, I may be wrong.

I’ve lived long enough, and learned from enough experience, to know that certainty is malleable. There’s a difference between what is fact, and what is truth. What I think I know for sure, I may in fact have no idea about whatsoever, because I’m missing key information. Whether because I haven’t looked hard enough, or because said information has been intentionally withheld, I can’t always say for certain that I’m reliably informed about the entirety of any given subject. And whatever the subject in question may be is often in direct correlation to how important it is to know enough information about it to confidently express an opinion you feel is, to the best of your knowledge, correct.

For example: if someone were to say they liked the books written by a particular children’s author (such as Enid Blyton, Dr. Suess, J.K. Rowling, or Roald Dahl), but they didn’t know anything about said author’s problematic personal beliefs (like Blyton’s general racism, Suess’ early racism, Rowling’s transphobia, or Dahl’s antisemitism), they wouldn’t therefore be actively promoting, condoning, or themselves believing in the harmful attitudes of those authors, because they were only in it for the art itself, not whatever the author had to say outside of that. Just because an author can be truthful and perceptive in their writing doesn’t mean they can be truthful or perceptive about the real world. And besides, there’s the “death of the author” delineation between art and artist that — depending on the medium, anyway — can sometimes reasonably be achieved.

However, if someone were to tell people not to wear face masks or change anything about their contact with other people during a deadly pandemic, because they believe it’s not all that serious, and the act of donning a mask is somehow a muzzling of their freedoms, and they act combative and defensive against everyone who tells them they’re wrong, but they only believe in this anti-mask stance because they happen to consume information from a handful of bad right-wing news sources… well then, that’s a whole other story. That’s deliberately choosing ignorance over verifiable information; that’s choosing your own comfort at the expense of others around you; that’s a dissemination of a false and potentially lethal opinion that can have devastating un-retractable consequences on human lives.

Those are two vastly different ends of the spectrum, of course, but it’s the kind of thing I think about whenever I try my utmost to make sure my opinions are as informed and well-rounded as possible, and that I am sure I could sleep at night believing in them, before I express them publicly.

As it was once so eloquently put by Oscar Wilde:

“Most people are other people. Their thoughts are someone else’s opinions, their lives a mimicry, their passions a quotation.”

Or as William Goldman famously said:

“NOBODY KNOWS ANYTHING.”

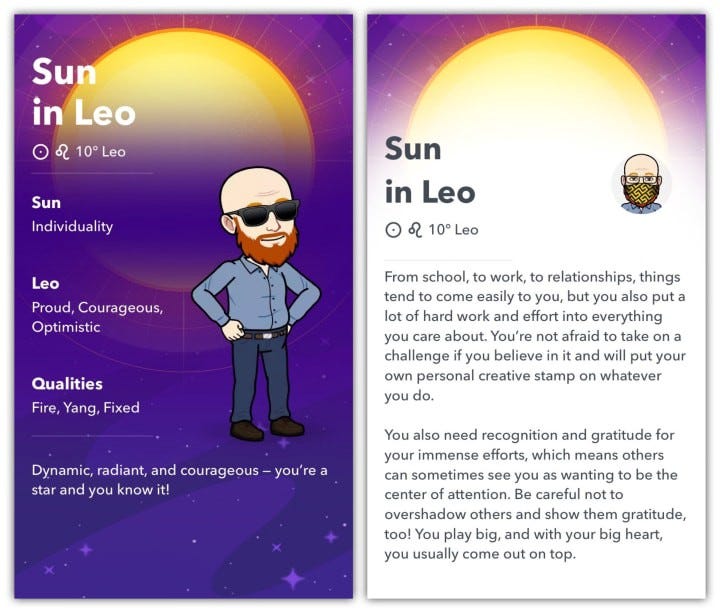

Oh, and while we’re still on the subject of being a Leo, here’s what Snapchat’s star sign calculator had to say on the matter:

Um… “things tend to come easily to [me]”?

If only they knew how phantasmagorically off the mark that statement was.

But we don’t have nearly enough time to get into that right now.

Now, I will say that Astrosofa’s articles regarding the so-called Taurus Ascendant and Moon In Aquarius signs do admittedly skew a smidge more accurate in describing my personality… except that’s exactly the perniciously annoying thing about astrology-type stuff, is that sometimes they seem right on the money.

But then again, a broken clock is right twice a day, isn’t it?

Horoscopes are like fortune cookies, Myers-Briggs tests, and BuzzFeed quizzes — they’re all vaguely right and vaguely relevant to your life, but that very vagary is what makes them so dangerously tantalising to invest a full-throttle belief in. It’s much like the cold-reading techniques fake psychics pull to pretend as if they’re reading your mind, or talking to ghosts of dead family members. They spout extremely generalised details that could apply to literally anyone — like “you care about someone… you’re facing a big decision… you’ve lost someone recently… you’re under great stress”, and so on — until just enough of these hazy statements accumulate for someone to relate to them so much that they can fill in the blanks with specifics from their own lives, thus confirming in people’s minds the psychic’s false legitimacy.

The thing I find the most frustrating about this, besides the fraudulent practitioners themselves, is when believers in these fields of magical thinking will employ so many mental gymnastics to maintain the illusion of credulity that’s required to keep the faith in their belief standing.

A benignly funny version of this phenomenon was memorably exhibited by Jenna Marbles in this old episode of the Jenna + Julien Podcast from late 2019, wherein Julien gave her names of celebrities, and Jenna would guess their star signs:

What’s illuminating about this is seeing how many times Jenna says a celebrity’s zodiac is X, Y, or Z, stating that they definitely exhibit the traits of this sign or that sign; but when Julien reveals the person’s actual star sign — which Jenna usually guessed incorrectly — she would then immediately backtrack and say “oh yeah, that makes sense, they’re totally that sign”, and then they repeat this process for the rest of the game.

In the past, when I’ve told astrology-believers that I’m purportedly a Leo, and yet I don’t feel like one, I’ve often heard a variation on the reply: “No but you definitely have that Leo vibe about you, you give off that energy.”

But a part of me wonders what would happen if I had told them I was, like, a Sagittarius or a Pisces or a Virgo or whatever. Would they say the same thing as before, but interchangeably say “you give off that [Sagittarius/Pisces/Virgo/etcetera] energy” instead?

On the more serious end of this equation, this behaviour is a manifestation comparable to the kind of goalpost-moving mindset that subsumes glaring contradictions to a belief, and spins them into mere blips on the radar that can be ignored with impunity, even if those blips would have earlier been seen as a deal-breaking challenge to the belief’s validity.

• That celebrity’s star sign is completely the opposite of what I thought? They must just share traits with another sign that’s kind of similar!

• That person’s great-great-grandfather didn’t fight in the war, and that other person didn’t have a dog when they were a child? The spirit medium must just be hearing the wrong ghosts!

• None of Q’s predictions in the QAnon forums about Trump and the Deep State ever came true? The radical liberal lizard people must just be burying the evidence, Q’s predictions will be right eventually!

• You can literally watch livestreams of astronauts doing spacewalks, and shots from cameras pointed at Earth from space, and immediately see that the Earth is globe-shaped? Pfft, as if, we know the Earth is flat, and NASA’s just using CGI and Photoshop, we’re not stupid!

Now I don’t mean to equate these differing modes of flexible-yet-immovable belief structures as all being on the same level of harmfulness. As with everything in life, it’s a lot more complicated than that.

What I am saying is that when this kind of elastic relationship to the truth within a belief system manifests in the worst places — conspiracy theorists, anti-feminists, incels, religious zealots, cult leaders, racist organisations, and so on — it allows people in those circles to fall for anything told to them by other members of those communities, and to reject anything told to them by anyone outside of those bubbles.

But it’s worth remembering that this ideological elasticity is a defence mechanism, of the sort I think everybody is familiar with having deployed at some point. It’s a wall your psyche puts up to protect you, because it hurts to be told you’re wrong about something, or you’re part of something bad. You don’t want to be hurt, so the instinctive reaction is to deny and defend your position, because confronting the inconsistencies, fallacies, and just plain falsities of a belief when they inconveniently (and inevitably) fall apart under the slightest scrutiny would mean you’d have to face the very real possibility that a belief you bought into was built on lies.

Nobody likes to look like a fool. But even if continuing to propagate an untrue idea only serves to make you look like a fool anyway, you will probably still cling to the denial that that’s what’s happening, at all costs, because it would mean admitting defeat, and having to deconstruct a huge part of your identity, which is painful and laborious and time-consuming and humbling… but worst of all, it can mean revoking your place among a community of like-minded people who you could once fall back on.

Most people just want somewhere to belong. A space where they feel seen and understood. Somewhere that’s a refuge from the negativity of the world. People just want to have kinship and purpose in a world often devoid of either.

It’s this normal human need for connection that can incrementally lead someone down paths towards toxic belief systems and toxic people, and this same connection that can make it so painfully difficult to break free for those who start to see the cracks.

Leaving behind a belief is one thing, but leaving behind a lover or a friend or a family member who may have lead you astray is a whole other story.

Perhaps an important contextual note to take into account is that when I was younger, I used to be a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, also known as LDS, also also known more commonly as the Mormons. (Trust me, the only Book of Mormon you need is the one with “Hasa Diga Eebowai”.)

This was not a choice made by me, but rather made for me by my mother, who for reasons I can only speculate decided to join the church in 1995 when I was two years old, thus volunteering me and my sister into the congregation along with her. Long story short, by the time I was sixteen, I had begun distancing myself from LDS, deprogramming my internal beliefs from what I’d been taught by the church, but especially from all the erroneous things I’d been told to believe about the world by my mother.

That’s a story to be told in full another time. Suffice it to say that my perception of how the world worked changed significantly during my mid-to-late teens. I pivoted away from seeing things as either holy or sinful cogs in the grand machine of the Lord’s unfathomable cosmic plan, in which everything that has ever been, or ever will be, is preordained from start to finish by God. In its stead, I switched to viewing the world as being an infinitely knottier tangle of chance, chaos, cultures, and circumstance that couldn’t so neatly be explained by the idea of theoretical outside forces shaping our lives from the heavens.

To clarify, though, I don’t mean this in the ultra-nihilistic philosophical sense that some religious people imagine atheistic people obligatorily adhere to in the absence of a belief in God; it’s not a case of being like, “oh, nothing matters, everything’s meaningless, there’s no afterlife, therefore there’s no reason or incentive to be good, so I might as well be bad!”

On the contrary, the conclusion I came to was that if our lives are fleeting and temporary and pointless in the face of the universe’s cold indifference (which is the wrong expression really, as it implicitly anthropomorphises the universe as not only having a consciousness we could comprehend, but one which has the capacity to feel coldness, or indifference, or any other human feelings in the first place), then in our existence’s vacuum of pointlessness, we have to make our own point, our own purpose for living.

Life in this world is indiscriminately random and cruel; it’s built atop multiple millennia of countless countries’ overlapping histories that have shaped our lives in ways we may never know or completely comprehend; we each have one life, and it can be snuffed out at any moment without warning; life is so fucking hard for the vast majority of people on this planet. So the absolute least we can do, during our brief borrowed time inhabiting this world, is be as kind, as empathetic, as understanding, and as decent as we humanly can.

Not to ulteriorly try getting something material out of it for yourself, nor to gain special heaven points to curry superficial favour with an omniscient overlord who would already know how bad or good you’ve truly been — ( looking at you, evangelicals!) — but just because of this simple fact:

We are all we have.

Easing the burdens of others when we can, redistributing the weight of the world to make it easier for everyone to carry, is one of the best things humanity is capable of.

As the eponymous Inspector in An Inspector Calls put it:

“We are responsible for each other.”

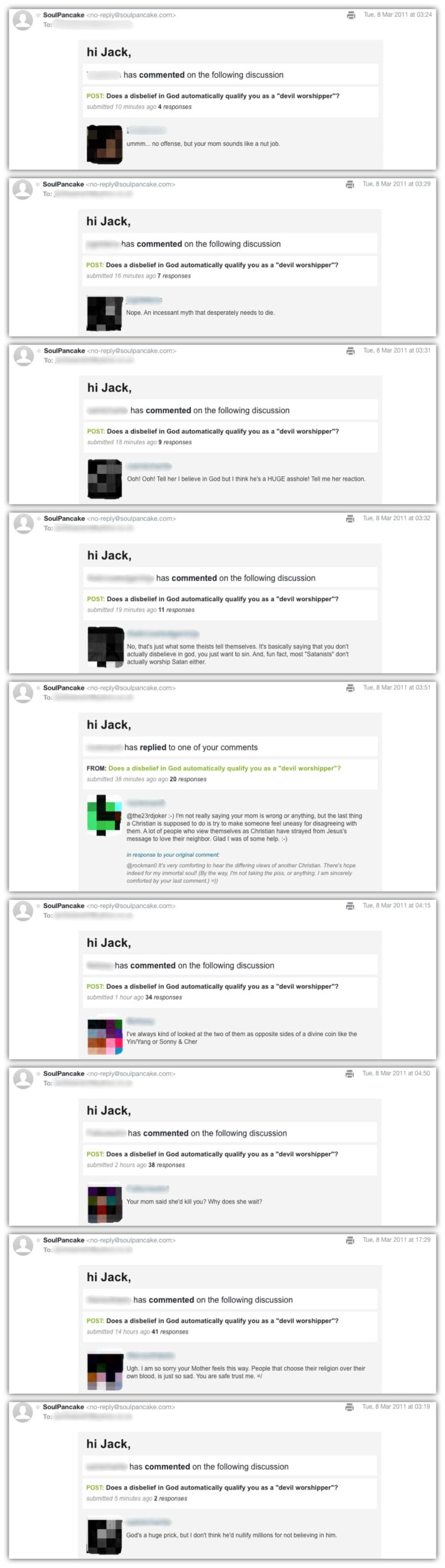

Now obviously, when I eventually mustered the gumption to tell my mother point blank in 2011 that I didn’t believe in LDS or Christianity or any sort of religious type stuff anymore, it did… not go down well. Indeed, this revelation lead to her tearfully informing me that my disbelief in God automatically meant I was now a devil worshipper bound for Hell, and that when Judgement Day came, and I’d by default be on Satan’s side of the battlefield, she — being on God’s side, naturally — would have no choice but to kill me during the great final war between Heaven and Hell.

So that was nice.

In fact, back when this happened, I posted a question on Rainn Wilson’s SoulPancake website, basically asking for other people to weigh in on whether or not this was a normal thing to say or think. (To her? Yes. To anyone else? Unquestionably not.)

This was back when SoulPancake still had a community forum sort of user base and interface for debates and discussions, which it evidently no longer has, so the only remaining evidence of my account, my question, and how others responded to my mother’s fire-and-brimstone rhetoric, lies within the archived email notifications I received with each new comment:

Here’s the bottom line.

Remember earlier, when I said to put a pin in my mentioning of free will?

Now’s the moment we circle back to that.

You see, back in February of 2020 — a month before the pandemic struck and the first national lockdown began — me and an old friend of mine, whom I’ve known for almost 13 years, were walking through Cardiff on the way to her bus stop. It was a cold winter evening, the streets were busy, and we had just come from having a meal after seeing Birds of Prey at the cinema. (It’s a great movie, by the way, you should watch it if you haven’t already.)

As we were walking, we got into a discussion about biological determinism, and whether we as humans truly possess free will. (Yes, I know this sounds like the start to a preposterous r/ThatHappened reddit post, but this is honestly the kind of conversations we find ourselves in.)

Having a view of the world that’s of a more nihilistic persuasion than my own, she was arguing from the perspective that because we’re born with various genetic predispositions we have no control over — hereditary traits, diseases, disabilities, sexualities, and what have you — we ultimately cannot really have free will, since everything we are, everything we do, and everything we want is all the result of coding within our DNA that dictates the course of our lives.

In finding the right words to articulate my counter-argument, I had a sudden epiphany of how best to convey the philosophy of my (respectful) repudiation, even if it wouldn’t sway her one way or the other.

The rebuttal I presented to her was along the lines of this:

Yes, from birth we are pre-programmed with a certain assembly of biological details that play a big part in defining the shape of our lives to come. So in that respect, our lives are predestined, and in many matters we are slavishly at the whims of parts of our minds and bodies we cannot change.

And yet, we still have free will.

Because we can choose to say “no”.

How?

Humans are stubborn like that. We can be told to do something that would be in our best interests, and for no good reason, we’d still say “no”.

Your body may be born with physical disabilities – visible or otherwise – that present challenges to living in a world catered towards conventionally able-bodied people, but you can still say “no” to giving up on living a life, and “no” to letting others treat you as less than human.

You may be born in the wrong body altogether, and you present as a gender you know is not your true identity, so you can say “no” to staying confined to an outward appearance that clashes with your inner self, and change yourself to whatever degree you see fit to reach that point of being truly you.

You may be plagued by intrusive thoughts of horrific deeds your brain is screaming at you to commit, but you can choose to say “no” to carrying those actions out in reality because you know they’d be wrong, and you don’t want anyone else to feel the way you do.

“No” can be self-destructive, but it can also be self-empowering, because it is one of the clearest signs humankind has that we have choice in what we feel, what we say, and what we do in our own lives, and other people’s.

The question that then follows is: will the conscious choices we make be beneficial, or detrimental?

All of this to say:

The stars don’t define us.

We define ourselves.

Originally published at https://vocal.media.