Run The Series: CUBE

What better description of the CUBE trilogy than that of its own construction?

(NOTE: This will not be covering the 2021 Japanese remake of the first film, but solely focusing on the original Cube trio released between 1997 and 2004.

Given the rotten reviews I saw for said remake when it came out, I don’t think anyone will mind its omission here too much…)

CUBE (1997)

★★★★½

“They may have taken our lives away, but we're still human beings. That's all we've got left.”

With some films, you forget the when, the how, and the why you came to watch them for the first time.

But with other films, they leave such an indelible imprint on you, that you can recall exactly the when, the how, and the why with crystal clarity.

Cube is one such film for me.

The when?

2005 - (already 20 years ago?!) - when I was 12 years old, and still in secondary school.

The how?

By watching it late one night on the UK's Channel 5, by myself, during a visit over Christmas that me and my mother paid to my sister and her boyfriend (now husband). I slept on an inflatable mattress in the living room every night we were there, and I had free rein of the TV during the late night/early morning before going to sleep, so long as I kept the volume low enough not to disturb anyone else, of course. I probably knew of the film's impending broadcast from reading a copy of TV Times magazine that was lying around, if not from seeing it advertised on Channel 5 itself ahead of its showing. I recall being so excited at being able to finally watch Cube for myself, especially as it hadn't been very long since I'd first found out about it weeks or months earlier.

The why?

Because it was recommended to me by a friend of mine, by the name of Ryan Harvey, whom I'd known since primary school. We were in the school's dining hall (in the chilly morning before classes began, getting breakfast at school because we couldn't at home, which is a detail I've just re-excavated upon this very moment of thinking back on it). We sat chit-chatting about this and that, when Ryan told me about this film he'd seen called Cube. Everything he told me of what it was about, without him ever delving into spoilers beyond the first five minutes, piqued my interest further and further with each new detail, and each new box it ticked among my filmic interests.

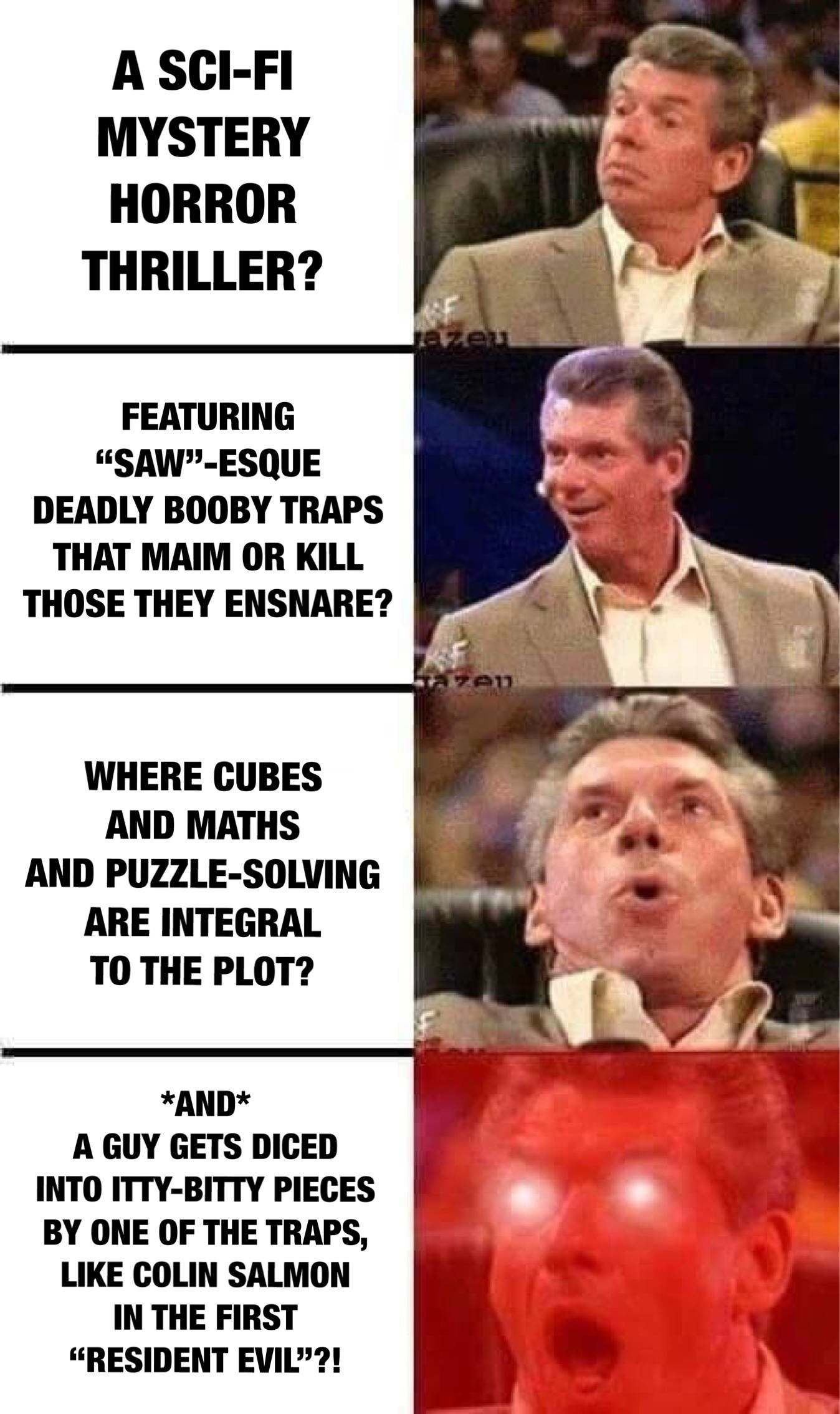

It's like that Vince McMahon meme, of getting increasingly impressed with something with every extra piece of information you learn, until your eyes glow blazing red in awe:

A sci-fi mystery horror thriller?

Featuring Saw-esque deadly booby traps that maimed or killed those they ensnared?

Where cubes and maths and puzzle-solving was integral to the plot?

And a guy gets diced into itty-bitty pieces by one of the traps, like Colin Salmon in the first Resident Evil?!

SIGN ME THE FUCK UP.

Lo and behold, I watched the film for myself that cold December night twenty years ago, the film periodically interrupted by adverts, yet still never losing its stranglehold over my imagination with its mind-bending intelligence, knockout practical gore effects, and sheer white-knuckle intensity.

This long-belated second viewing of Cube has been two decades in the waiting (the occasion being that I'm drawing up an article of films and TV shows that are in a similar vein to Severance - which has just finished its second season, as of writing - and the Cube trilogy ranked among the most pertinent examples I could think of that parallel the themes of Severance quite perfectly), and I'm happy to report that the film still absolutely rips.

Blah blah budget limitations, blah blah not-so-great moments of CGI, blah blah occasionally over-the-top acting-- WHATEVER, IT GOES SO HARD, and director Vincenzo Natali beautifully wrung every last drop of dread and suspense out of this premise with palm-sweating aplomb.

The jittery handheld wide-angle camerawork.

The sparse electronic score by Mark Korven (whom I wouldn't hear of again until 2015, with his work on Robert Eggers' The Witch).

The clammy sweat-drenched atmosphere of tension accentuated by the moods of the cubic rooms' different colours.

The ungodly stress of solving complex mathematics.

The unnervingly mechanical, muffled rumbling sound design (which, when coupled with the ahead-of-its-time horror of unearthly liminal spaces, evokes the labyrinthine infinite innards of the house on Ash Tree Lane from House of Leaves).

Put all those elements together, and you have a film that is cemented as one of my all-time favourites.

Between this film, 2004’s Cypher, 2009’s Splice (which has garnered a surprisingly outsized reputation for pissing off and grossing out people more than I'd realised), and his TV work that's included directing episodes of Hannibal, I've always been curious to see what Natali does next, ever since Cube formally introduced me to his work all those years ago.

Not to mention, in these apocalyptic-feeling days of billionaire fascists, wannabe dictators, widespread warranted distrust of our police and surveillance states, and the inescapable control that capitalist corporations have over our collective lives, Cube's virulent paranoia and frantic-yet-rational theorising, as to why the eponymous contraption of the story even exists, rings all the more horrifying in its prescience, and even worse, its plausibility.

Before Cube 2: Hypercube got too silly with the premise, and took things into literal other dimensions that defy all suspensions of disbelief alongside the defiance of the laws of physics, the original Cube's grounded fears - over the how and the why its unseen outside world could create such a colossal, faceless mechanism for inflicting suffering and despair - feels more sickening in its metaphorical power and relevance today, than it did nearly 30 years ago.

CUBE 2: HYPERCUBE (2002)

★½

- “Sixty thousand, six hundred and fifty-nine rooms? Christ.”

- “This place must be huge.”

- “Oh, yes, yes. In a hypercube, there could be 60 million rooms!”

It doesn't take a mathematician to calculate that Cube 2: Hypercube both sucks and blows.

Everything that made Cube so special and thrilling gets summarily dumped, in favour of a terminal case of sequelitis that ups every ante to preposterous degrees that show a fundamental misunderstanding of the first film's appeal. Where the original sported the intelligent instincts of the direction from Vincenzo Natali (of Cypher and Splice fame), and the screenplay co-written by a pre-Orphan Black Graeme Manson, this sequel has no input from any of its predecessor's masterminds, and it shows. Badly.

On paper, there's nothing necessarily wrong about maximising the scale and stakes for a Cube sequel, nor even with making a giant leap into the quantum unknown by adding parallel universes, time and gravity manipulations, geometric traps, overlapping duplicates of the same characters, and tesseract-related nonsense to the mechanics of this bigger, badder cube. But as with most things, it's all about the execution, and Hypercube's execution is a dud on almost every count.

The acting? Appalling, as it strands even Canadien-er Canadien actors with a listless script you'd nowadays derogatorily say sounds written by A.I.

(Ironically, one of these actors is Kari Matchett, whom I first saw in the 2005 sci-fi drama series, Invasion, which I just so happened to start watching during the very same window of time I saw the first Cube twenty years ago!)

These characters are uniformly one-note, inconsistent, and straight up garbage, spouting first-draft placeholder dialogue that never got refined or punched up into sounding natural. Geraint Wyn Davies - often looking a lot like latter-day “Rowdy” Roddy Piper - does battle with his native Welsh accent as he audibly struggles to wrap his mouth around Americanised pronunciations. Matthew Ferguson looks and sounds distractingly like Bethesda's Todd Howard, and is even written to have a backstory as a games designer. Lindsey Connell is relegated to being eye-candy in a fancy red dress that visually pops against the stark fluorescent white lighting of all the rooms (which is another of the film's miscalculations: removing colour variation to differentiate the rooms from one another).

There's even more characters, and that's its own problem, too. The exact same quandary as Saw II, and really, every other sequel in any genre that's ever shot themselves in the foot by increasing the quantity of characters to unsustainable levels, robbing the film of requisite focus and decent characterisation to make you care about what happens.

The traps? Also rubbish. Remember, the first film's selection of traps were tactile and visceral, even when CGI was used to render them, because they were all based on things you could comprehend as causing bodily harm: acid, fire, and razor-sharp wires. Not to mention they were all engineered as tensile reactions that sprang to life from stimuli by the cube's prisoners setting them off through sound, movement, or pressure. But in Cube 2, they're all arbitrary VFX concoctions that have no rhyme or reason. Nobody tensely enters each room afraid of setting off a new trap (as those in the first Cube knew to be, hence why they'd use their boots as canaries in the coal mine to test for trap sensors in every room), because in this dumb-as-rocks sequel, the traps obediently follow the whims of the plot and the characters talking through exposition, before they finally decide to go off randomly and do their jobs of imperilling the characters’ lives. And even then, they're just abstract geometric constructs with sharp edges for slicing and decapitating, rendered in low-budget early-2000's CGI - (at one point bearing a remarkable resemblance to the body-shields in David Lynch's Dune, and looking just as dated) - and they are neither realistic enough to feel believably threatening, nor uncanny and strange enough to be frightening in their otherworldliness. Which theoretically could have been a route that worked, were it not for the overall execution.

And the ending? What a load of pish (not a typo). Beyond the Langoliers-looking whirlwind of cheap and bad visual effects it devolves into, the story tries to have its cake and eat it too, with a conclusion that wants to have a big twist about a character's motivations to change what we thought we knew of them, put a name to the forces behind the entire enterprise, and still keep things so ambiguous and unanswered that you don't feel like you learned anything substantive. It opens up the claustrophobic world of Cube, yet tells you nothing you couldn't have already surmised by yourself, or through the guesswork made by the characters in the first film. It wants to over-explain, and under-explain, but as the first film exemplified, the who and the why of the cube is less important than the emotional and psychological impact of being trapped within it, and the immediate need to survive the surreal situation long enough to escape, if possible.

Actually, come to think of it, I said something nearly verbatim regarding this point when I wrote about M. Night Shyamalan's Old a few years ago!

Speaking of whom:

Cube 2's director is one Andrzej Sekula, pulling double duty as the film's cinematographer. This is one of the few aspects to the film I thought was somewhat good, if not at the very least interesting, and it put me in mind of whenever M. Night Shyamalan's lesser films may fail in their ambitions because of his writing, but at least have inventive visual storytelling techniques to highlight that even if the overall film didn't come together as well as anyone would've wanted, it certainly wasn't for lack of trying in the effort and creativity poured into other elements of the production.

And so it goes with Hypercube, where Sekula seemed more within his element experimenting with camera placement and angles and dynamism of movement, while comparatively foundering with knowing how best to get good performances out of his ensemble of actors who already struggled with the terrible script's terrible dialogue.

This made me curious to see what else Sekula had done, and upon checking his list of credits on Letterboxd, imagine my shock to see that he was the director of photography on... Reservoir Dogs?! AND Pulp Fiction?!! AND American Psycho???!!!!

Yowza. I mean, hey, cinematographers can go on to do great work when directing their own films (e.g. Jan de Bont, Barry Sonenfeld). But here, it would appear Sekula fell under that curse of acclaimed cinematographers making less-than-acclaimed films when they became directors themselves (e.g. Janusz Kamiński with Lost Souls; Wally Pfister with Transcendence; and coincidentally another Andrzej, this time being Andrzej Bartkowiak with Cradle 2 the Grave and Doom).

But hey, we can't all have 100% hot streaks in everything we do, can we? And if you're lucky enough to have a foot in the door of the entertainment industry with your profession(s), work is work is work, wherever you can get it. Cube 2 is a bad film in virtually every respect - bad editing, bad writing, bad acting, bad pacing, bad effects, bad everything - but despite it being bafflingly boring at times, at least the people who made it were clearly attempting to make something fun and interesting. And with all the time travel, duelling doppelgängers, tesseracts with no affiliation to Marvel or Interstellar, and a zero-gravity fast-forwarded rotisserie sex scene with billowing fabrics blown by off-screen wind machines—

—you can't say they didn't try.

CUBE ZERO (2004)

★★★

“There's a purpose, and there's a plan. And I'm not so stupid as to think there's no plan just because I don't understand it! Here's a news flash: we're just the button men.”

I began this recent rewatch of all three Cube movies for the purposes of an article I'm drawing up that's compiling a bunch of films and TV shows reminiscent of the incredible Dan Erickson/Ben Stiller show, Severance. I included the Cube trilogy in my list, because in the little vestiges of plot I could remember from having watched them so many years ago, there was some strand of DNA one could see shared between the Cube series, and the themes and plot of Severance.

As this memory-refresher has made me realise, most of those points of comparison come directly and solely from Cube Zero.

Follow my analogy:

A tiny workforce composed of only a few people, isolated from the rest of the world, holed up in a building on a floor with no access to sunlight, in a tiny department dedicated to carrying out menial yet unnerving tasks for a giant mysterious organisation with cultish religious fervour baked into the rigorous protocols everyone is expected to slavishly follow, where said organisation performs sinister experiments on people that involve surgically implanting chips, erasing memories, manufacturing consent, and exerting control over the employees to comply with the company's bidding through manipulation and intimidation.

Am I describing Severance, or Cube Zero?

Obviously both, otherwise why else would I write the above paragraph in such a leading manner? Though of course, to retrofit the two into similarity, one has to remove key contextual details that distinguish them from another - like how Severance doesn't (yet) have people trapped in a giant Hellraiser-esque puzzle box filled with littler puzzle box rooms containing deadly traps, and Cube Zero doesn't have goats, or darkly comic satirical levity, or the benefit of/budget for world-class writing and directing - but if you squint, you can see the faint outlines of the commonalities between them that I did, too.

Now, out of all the Cube films, the first will always be the best, the second (Hypercube) will always be the worst, and the third (Zero) will always be the one with the gnarliest practical gore, for it includes a scene that fucked me up so badly when I saw it as a kid, it singlehandedly got this film onto my list of “Films That Have Fucked Me Up The Most”.

The scene in question? The opening kill with the guy getting slowly disintegrated by acid - an echo of the original film's acid-kill that just had the character of Rennes get sprayed in the face until his skull was hollowed out, but here the concept is amplified to have this random cannon fodder dude completely coated in acid, think he's safe because he's not immediately in pain, desperately lick the fluid from his skin because he's so dehydrated, only to realise it isn't water, and he slowly begins to blister and peel away into globules of sizzling flesh and puddles of blood, until he tears away the skin and flesh from his own face, screaming in agony, collapsing and melting into nothing but goo and bones. (I can't remember the chronology of which I saw first, but I know that there was a very similar sort of death scene in an episode of Alias1 that disturbed me almost as much, and several years after both of these examples, I happened upon a clip online of the “roach motel” kill from A Nightmare on Elm Street 4: The Dream Master, and I think what these all have in common is they all bear visual similarities to my root horror movie trauma of witnessing the tearing-the-face-off-in-the-mirror sequence from Poltergeist when I was a wee lad. The body horror stuff from David Cronenberg’s The Fly surely had to have contributed to this abiding fear of melting faces and bodies that conceptually links all these sequences together, but for some reason, it’s Poltergeist that lingers most stubbornly in my memory as the primary cause for this pernicious ick.)

Watching this sequence in Cube Zero again for the first time in close to two decades, I'm relieved that it doesn't look real enough to my eyes anymore to freak me out the way it used to. I always recalled there being no cuts in the shot where the man uses one hand to pull his face off, but this memory was evidently faulty, for there is a cut and an extra insert shot between the moment he reaches for his face, and the moment the skin and flesh is pulled from the prosthetic skull, so being able to recognise the practical trickery implemented to achieve this gag really helps put my old fear of this kill scene to bed. It's an impressively done moment that's putridly grotesque (complimentary), and sets the tone for Cube Zero being a sizeable improvement upon its miscalculated predecessor, Hypercube.

And while the rest of Zero can neither live up to the expectations set by its opening scene, nor come anywhere close to reaching the freshness and simplicity (for lack of a better word) of the original Cube, I can't help but still have a soft spot in my heart for this third instalment in the trilogy.

Yes, it's still a fundamentally unnecessary addition to Cube lore, which you can pick and choose to keep or disregard as canon as you see fit (just as you can choose to see it as a prequel or a sequel, because nothing in the film discounts either option).

Yes, it looks and feels like an early 2000's Syfy Channel2 TV series (which on the plus side means it's still shot on 35mm film, but on the negative side means the dated CGI and the editing choices make it look as cheap as it probably was).

Yes, the score by Norman Orenstein (returning from Hypercube) is often intrusive, at best being what you might describe as chintzy with its endless usage of Indian tabla percussion samples that make everything sound like scenes from Dangonronpa: Trigger Happy Havoc, and at worst being laughably terrible when it goes the route of adding what sounds like a saxophone (performing an initial three-note motif I swear is cribbed from Bernard Herrmann's Taxi Driver score), and most egregiously, an accordion performing cartoonish circus music when the company's goons enter the story halfway through to salvage the disobedience taking place.

And yes, you may take a great dislike to the film if you don't vibe with those aforementioned goons (including a very young Diego Klattenhoff, pre-Homeland and The Blacklist) veering the film into a jarring tonal shift towards the campily goofy, thanks to that stupid clownish accordion, and especially thanks to actor Michael Riley making a three-course meal out of devouring the scenery with his hammily villainous character, Jax. (He made some all-caps CHOICES with his performance here, and you know what, I think it's fun to watch him have fun with it.)

But when it gets down to the business of brutal practical gore, inventively sadistic traps, and using the creation and existence of the Cube to pay lip service to dystopian ideas that feel queasily topical with every passing news story on any given day nowadays, Cube Zero is just about a worthy enough successor to Natali's nonetheless unsurpassed original film in the series. Or at the very least, it's nowhere near as complete an embarrassment as Hypercube, which is a credit to the third film's writer/director, Ernie Barbarash, maybe learning from the mistakes he saw made during the making of the second movie.

And hell, Cube Zero's final cruel twist even manages to recontextualise a portion of the original Cube's plot in a way that newly informs, and perhaps improves upon, that film's most poorly-aged facet, with the resulting horrifying implications bringing the series full circle in a neat little nihilistic bow.

On a couple of incidental tangents:

• It's old hat at this point to remark on how closely Cube and Saw feel related to one another, superficially or not. But Cube Zero feels the most like a Saw movie in all but name, to the point where you'd think this was ripping off Saw virtually whole-cloth. Yet that couldn't be the case... right?

I mean, Cube Zero has all the visual hallmarks of the Saw aesthetic (i.e. the grungy green lighting/colour grading, bearing a strong resemblance David A. Armstrong's series-defining cinematography on Saw 1 to VI; the rusty industrial metal rooms; the elaborately engineered traps that cause violently gory deaths, though of course that detail was Cube’s forte long before Saw)… Orenstein’s music during the acid-death cold open sounds remarkably similar to the industrial soundscapes of Charlie Clouser’s Saw scores… and the film was distributed by Lionsgate, with the credits even preceded by the grimy “LGF” ident the studio used during the first couple of Saws (prior to the “cogs and gears” idents that Lionsgate would use for many more years later on).

But the first Saw hadn't yet come out in theatres, let alone emerged as the gargantuan cultural juggernaut of an IP it swiftly became, during the time that Cube Zero was in the making, so I'd hesitate to say one film was ripping off the other, since - according to IMDb's information (however reputable it may be) - Cube Zero was in production in Toronto between August 11th and September 5th of 2003, and Saw was in production in California between September 15th and September 21st of 2003, with both films’ subsequent days of shooting only barely overlapping. But since each was a Lionsgate production, maybe there was a crossover in knowledge of one another somewhere down the line? Maybe both films look so visually alike because they were following a house style prescribed by Lionsgate? Or maybe I'm forgetting how popular and influential the industrial/nü-metal music videos of the 1990's and 2000's were, and how much these films reflected those styles more than anything else. I don't know, I'm thinking out loud, and taking you along for the ride. My apologies.

• Also: lead actor Zachary Bennett herein looks like Will Poulter had a baby with Scott Foley in Scream 3, and once that thought hit me, I couldn't shake it, and now it is yours to be stuck with, too. You're welcome!

If you enjoyed this edition of Run The Series, you may be interested in perusing the previous instalments of this strand of film franchise retrospectives, which you can check out down below:

(Season 4, Episode 14 - “Nightingale”)

(or, as it would’ve still been spelt at the time, “the Sci-Fi Channel”, which is how I’d grown up with it being spelled as such)

Why do I want to feel like the "Cube" movies exist in the same universe as Vincenzo Natali's "Nothing"?

Fromtheyardtothearthouse.substack.com